|

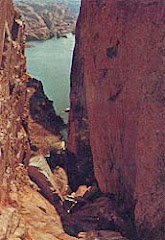

| Hole-in-the-Rock: When the wagons went down this trail it was twice as long as it is today |

Written by Georgia Robb Drake, grand-daughter to Heber William Robb.

In studying the historical reports and diaries of the Hole in the Rock participates, as the time neared there was much excitement and anticipation for this new adventure to begin. Throughout the summer of 1879, while emigration routes were being explored, families were rounding up livestock, disposing of property and acquiring sturdy wagons, necessary supplies and equipment. "Ho for the San Juan" became a common greeting throughout Southern Utah. Yes, I was concerned for those families, men, women, and children, full of faith, enthusiasm and courage, ready to take on an unparalleled expedition in untamed territory. Trusting scouts who were sent to determine the best route and feasibility of road building through the broken terrain returning with favorable reports, had done their job well. Trusting the land would be suitable for farming, trusting mostly in God.

A Utah newspaper described Utah's southeast corner in 1861, as "one vast continuity of waste and measurably valueless, except for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians and to hold the world together." The Mormons wanted to establish an outpost settlement to bring the word of God to the Indians and act as a neutral point of rendezvous of the southern Navajo tribes, and the war-like Ute and Paiute tribes to the north. Many of those who inhabited this area did so by raiding and pillaging the Mormon settlements west of the Colorado. "One writer reported that at one time twelve hundred head of stolen cattle were driven across the Colorado at the Crossing of the Fathers. Losses to the raiders, in sheep, cattle, and horses, were estimated at more than one million dollars a year."This was such a harrowing experience, the accomplishment of those who went through the "Hole" is remembered with great respect. Then I wondered, would I have gone if I had been called? The answer is, Yes. I hope I would have the same faith and courage these brave pioneers showed, and retained under such adverse situations.

Great Grandmother Sarah P. Holyoak Robb worried about the outlaws who had made the difficult terrain their home. It is said that Solomon Wardell urged Sarah not to go on the expedition. Whether he did or not, Sarah, her husband Adam Franklin Robb and two sons, Albertus (4) and William Heber (2) were among those daring pioneers of the San Juan Mission. Adam's brothers George Drummond Robb and family, William and his family, John and family were also among those called. John also known as Jack and Thomas were driving a head of cattle to the San Juan.

In studying the historical reports and diaries of the Hole in the Rock participates, as the time neared there was much excitement and anticipation for this new adventure to begin. Throughout the summer of 1879, while emigration routes were being explored, families were rounding up livestock, disposing of property and acquiring sturdy wagons, necessary supplies and equipment. "Ho for the San Juan" became a common greeting throughout Southern Utah. Yes, I was concerned for those families, men, women, and children, full of faith, enthusiasm and courage, ready to take on an unparalleled expedition in untamed territory. Trusting scouts who were sent to determine the best route and feasibility of road building through the broken terrain returning with favorable reports, had done their job well. Trusting the land would be suitable for farming, trusting mostly in God.

A Utah newspaper described Utah's southeast corner in 1861, as "one vast continuity of waste and measurably valueless, except for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians and to hold the world together." The Mormons wanted to establish an outpost settlement to bring the word of God to the Indians and act as a neutral point of rendezvous of the southern Navajo tribes, and the war-like Ute and Paiute tribes to the north. Many of those who inhabited this area did so by raiding and pillaging the Mormon settlements west of the Colorado. "One writer reported that at one time twelve hundred head of stolen cattle were driven across the Colorado at the Crossing of the Fathers. Losses to the raiders, in sheep, cattle, and horses, were estimated at more than one million dollars a year."This was such a harrowing experience, the accomplishment of those who went through the "Hole" is remembered with great respect. Then I wondered, would I have gone if I had been called? The answer is, Yes. I hope I would have the same faith and courage these brave pioneers showed, and retained under such adverse situations.

Great Grandmother Sarah P. Holyoak Robb worried about the outlaws who had made the difficult terrain their home. It is said that Solomon Wardell urged Sarah not to go on the expedition. Whether he did or not, Sarah, her husband Adam Franklin Robb and two sons, Albertus (4) and William Heber (2) were among those daring pioneers of the San Juan Mission. Adam's brothers George Drummond Robb and family, William and his family, John and family were also among those called. John also known as Jack and Thomas were driving a head of cattle to the San Juan.

They were not just pioneers, before they left, each had been called on a mission. The San Juan Mission. They were more than pioneers, they were missionaries with a call to colonize the four corners. Among this incredible band, were two professional road builders. They were paid $1.50 a day, very good wages for that time. When they joined the group, the pioneers had already taken the wagons down the first huge obstacle, "The Hole". Other equally daunting challenges lay ahead. When they came to the next mammoth task, the paid road builders could not conceive of an answer to the challenges they had to overcome. Overwhelmed, they finally gave up and went back to Salt Lake City, saying it couldn't be done. Meanwhile, the Missionaries filled with faith in miracles and undying determination faced those same obstacles together. They solved their problems one after another until at long last, they reached their destination. Starvation, freezing cold, hostile Indians, impossible feats of engineering and road building. They faced them all with faith and courage, and proved their worth with every footstep.

I suspect the members of the San Juan Mission would tell anyone who questioned the wisdom of taking on such a harrowing journey, that their faith grew and miracles were experienced by all. Today, anyone who looks at the extreme grade and narrow passage of the Hole in the Rock must do so with awe and wonder. I am grateful my great grandparents were faithful in their role. Not all stayed after they arrived, but none left without first receiving an official release from their mission call. My grandfather William Heber Robb was only about 2 years old when he participated in this epic journey.

|

| We Thank Thee Oh God |

By David Miller

Appendix XI pp. 208

THE GEORGE B. HOBBS NARRATIVE

In Chapter VII of this work George B. Hobbs tells of the experiences of himself, George W. Sevy, Lemuel H. Redd, Sr., and George Morrell who were sent from the Hole-in-the-Rock to scout the country ahead in an attempt to locate a possible route all the way to Montezuma. The narrative found on the following pages is a continuation of Hobbs’ account in which he tells of his second expedition from the Colorado River to Montezuma, this time with provisions for the relief of the families which had been located there since the previous summer.

This account is copied from the San Juan Stake History, L.D.S. Church Historian’s Library.

After working some time on the road, which the company at the Hole-in-the-Rock were making by blasting, etc., down to the Colorado River, I returned to my camp at Fifty Mile Spring to get supplies and my mules in order to join Dan Harris on a return trip with supplies for our people who were starving at Fort Montezuma. Making inquiries from those who had promised to look after my mules while I had been away [on the exploring expedition] I discovered that they had neglected to keep their promise, and no one knew anything about my mules or where they were. Riders had been back as far as Escalante and had practically traveled all over the section of country lying between the Kaiparowitz Plateau and the Escalante Gulch, and no one had seen my mules since I had left. I started out to find them, going about 6 or 7 miles from camp. But finding no grass whatever I knew my animals would not stay in such a desert county. My belief was that they would try to make for their former home in Parowan. Returning to camp with this belief, I decided the next day that I would quit the camp altogether as I did not like the way the brethren had treated me in this matter, while I had been exposing my life to explore the road for them.

Therefore, I set out alone early one morning, in February [January] 1880 with a supply of crackers and my blankets with the intention of returning to my home. After going a mile or so I was impressed to lay my griefs before my God and kneeling on a smooth rock I uttered a few words of prayer, asking God to direct me in what I should do. The impression came to me that I should keep to the west side of all horse tracks. This I did, and after traveling a short distance I found some tracks leading up the steep barren clay hills toward the Kaiparowitz Plateau Cliff. I followed the tracks almost to the cliff where I found a narrow bench covered with abundant bunch grass, and here were my mules, fat as they could be, together with one other animal which the company had thought dead. This happy discovery came, as I always believed, as a direct answer to my prayer. Once before, when on my first trip, my prayers had been answered in a similar way, when I besought God to direct me which way to go, we having lost our bearings. He answered it by impressing me that I should follow the canyon to a certain place where I found a large cottonwood growing. This I did and found it was the only way we could get out. This simply meant the saving of our lives as we were starving, being without food in the cold snow, after having lost our trail.

Dan Harris returned from Escalante with supplies, and as it had been prearranged that I should return with him to bring supplies to those at Montezuma, we traveled together to the Hole-in-the-Rock near the Colorado River and then crossed the river, I fording the river with my horses, his horse being already on the other side. Taking our supplies in a boat, we camped about three miles on the east side of the river the first night. A heavy snow storm overtook us, and as the indications were that it would continue I refused to go further until the snow abated, starting it was better to have the snow under feet than over head. Bro. Harris became quite angry at my suggestion to stay a day or so and went [pp 210] back to the river where he persuaded two California miners (father and son) who were with the party to accompany him.(1)

Some of the brethren had gone about four miles further ahead to work on the road in order to make it easier for us to get out with our pack animals. When Bro. Harris passed these men they asked where I was. He answered that I had refused to start in the snow storm, and he was glad of it, as I wanted to go by way of the Elk Mountain, and he knew he could go up the San Juan. He then said, “Tell Hobbs that I will meet him on the road.” It pleased the brethren to think that a shorter way might be found, as I had held to my opinion that my way was the only way to get through.

I now stayed and worked on the road three weeks longer as I wished to get my wagons across the river. (2) The storm continued most of the time. When I got ready to start I asked for a volunteer to go with me but none would go. Bro. Sevy said no man could live and go through those cedars with the snow which must be on the ground. I said that I would go, as I would never live to know that women and children were starving to death for the want of an effort on my part.

The next morning I placed the packs on my mules, tying the head of one to the tail of the other and leading the first one. In this way I traveled the entire distance, going on foot myself. The second day, when I cam to the slick rocks, I looked back and saw a band of horses following me with men driving them. When they reached me at the bottom of the rocks I found it was Jack and Adam Robb, formerly of Paragonah.(3) They told me they were going to leave their horses at the Lake and accompany me through, as they had been off their homesteads near Farmington, New Mexico, for six months and were afraid someone might jump their claims.

We made good time, following the back bone or dividing ridge between the Colorado and San Juan Rivers toward the Elk Mountains, the snow getting deeper every mile we traveled. The weather was so cold that the snow was not crusted. Five days I spent in these cedars and gulches with the snow up to my chin. I had to cut trees out of my way in order to get through and my mules did not have a mouthful of food during this time. On Feb. 22nd, 1880 (my 24th birthday), I got out of this deep snow into a branch of the Comb Wash where the ground was bare. Here my mules would eat a little grass and then roll in the sand, which seemed to give them much pleasure, after being in the snow so long. The next day was good traveling down the Comb Wash.

Passing the Harris camp (4) the following day I reached Montezuma. Geo. Harris road out overtaking me, (5) asking me how long I had been on the road. I answered that this was my ninth day. He said, “You have made good time.” I asked him when Dan Harris had got through. He said “Yesterday,” and explained that he and his companions had eaten up all his supplies. He had been wandering in the deep snow 29 days (6) from our camp in the Hole-in-the-Rock. Geo. Harris desired to buy some of my supplies but I stated that no money on [pp. 211] earth could buy them, as they were sent to relieve those who were starving at Montezuma.

George and his brother Dan immediately got ready to return on my tracks to the main camp, which they did, reaching the camp at Cheese Ranch, about 10 miles east of the Colorado River. Inquiries were made as to whether they had seen me. They answered, “Yes, he got through, and for God’s sake if there are any of the rest of you that want to get through, you had better follow his tracks!”

It was a joyous moment for those starving Montezuma people when they saw me coming over the hill with the white sacks of flour on the packs. They had been watching for nearly a week, as the 60 days of promise were just expiring (my companions having on our first trip stated we would return with food in 60 days, they believing they could hold out that long).(7) They had but one pint of wheat left when I arrived and had not tasted flour for over four months. I stayed with these people 20 days while the Robb boys went up to Farmington and worked on their homesteads. Upon their return I joined them.

Just previous to our return a cowboy carrier [courier] had brought word to Montezuma Fort that the White River massacre (in which the Meeker family were massacred by Indians) had occurred and for us to be on the lookout as well as those at the fort.(8) Before leaving the camp at Cheese Ranch I had agreed upon a system of signals on any prominent ridge that I might cross to guide the company which way to come, my signals were three fires in a triangle. On the third way out we were making toward the Elk Mountains, arriving at a prominent ridge about noon. I made my first signals, which were immediately answered by a signal fire on the side of Elk Mountain. We were pleased to think that we would be with company again that night. No sooner had we started towads their fire in the afternoon and gone down into a box canyon than we came across the fresh trail of the Indians fleeing into the country west of the Elk Mountains. They had passed but an hour or so before. Not knowing whether the fire we had seen was an Indian’s signal fire or our friends, made our going dangerous, as we expected to be shot from every turn in the trail, my companions preferred that I go in the lead, they keeping well behind. I still had confidence in my God that he would preserve us, as he had done before. We found by the sign which the Indians’ horses had left that we were gaining on them as it made traveling for us much better than for them as they beat down the snowdrifts.

These Indians ran into our brethren’s camp about an hour ahead of us, retreating into the hills immediately not knowing but what our people were hostile toward them. They sent a squaw in, and our people gave her some clothes and food. Then others ventured in, they asked about us, but the Indians said they did not know anything of our whereabouts, although we were behind them. The men immediately came to the conclusion that they had killed us as they seemed so ignorant of our whereabouts. Six men immediately started out back on their trail expecting to find our dead bodies. They met us about half a mile from their camp. I then told them of the Meeker massacre and that perhaps [pp. 212] these were the Indians that were getting away. They immediately threw out guards to protect the camp and stock.

They had agreed to bring my wagon with them, but I learned it was where I had left it. This necessitated me going back after it. I met many different parties that were on their way to catch up with the main camp which was now at the Elk Mountain. The weaker ones were in the rear, some had an ox and a mule hitched together, some had cows and heifers in their teams, one I noticed was a pair of mules with an ox on the pike with a young girl riding the ox, to keep him in the road, all made inquiries of me how far it was to San Juan. The Robb boys accompanied me back as far as the Lakes staying there four days while I returned alone to Cheese Ranch for my wagon. In places where I could not get up the hills with my load wagon (having no help) I packed the supplies from my wagon onto pack mules, then came back for the wagon.

On April 4th, 1880, we overtook the main company at a place now called Rhen Cone on the San Juan River. (9) Next day we pulled up a steep dug way that had just been completed, (10) and the following day (April 6th 1880) we arrived at the point on the San Juan where Bluff City now stands. Much disappointment was experienced by members of the company of about 225 souls on their arrival for they had expected to find a large open valley, instead they found a narrow canyon with small patches of land on each side of the river. Wm. Hutchings of Beaver was the man that named the place Bluff City on account of the bluffs near by.(11)

The next day (leaving camp here) I pulled up to Ft. Montezuma which was my destination. The company now began the general work of colonizing, taking out the water, building water wheels, putting in crops, etc. I had promised Silas S. Smith who was captain of our company who was home at Paragoonah that I would let him know when the company got through, I just had time to scribble a letter to him sending it to Mancos (125 miles away) by a cowboy who was just leaving, to that effect, this being the first news to get back to Utah of the company getting through.(12)

Footnotes

1- Hobbs, and Harris had camped on Cottonwood Creek when the storm struck. These California miners are mentioned in numerous accounts but are never given further identification.

2- During this time Hobbs did get his outfit across the river, probably coming across with the rest of the wagons from Fifty-mile camp late in January 1880. He took his wagon as far as Cheese Camp before finally setting out with packs for Montezuma, as is “indicated by later references in this account. Although Hobbs uses the plural, “wagons” in this one place, it seems quote obvious that he had but one.

3- Platte D. Lyman’s journal entry for February 15, states that four men started for the San Juan with pack animals that day. This number probably included Hobbs, and the Robbs. This checks about right with later statements by Hobbs, that he arrived at Comb Wash on February 22 and at Montezuma two or three days later, having traveled 9 days from Cheese Camp. James Dunton and Amasa Barton had also taken a herd of horses ahead of the main company from Cheese Camp, according to the Lyman record.

4- At the site of Bluff.

5- George Harris rode out of the Harris camp at Bluff and overtood Hobbs as he was passing by on his way to Montezuma.

6- Hobbs had spent nine days, having left Cheese Camp February 15. He and Dan Harris had originally crossed the Colorado to begin their trip together about January 23 or 24.

7- In his Desert News (December 29, 1919) account Hobbs says: “I having on my first trip stated I would return with food in 60 days.”

8- For an account of this massacre see LeRoy R. Hafen (ed), Colorado and its People, I, 381-86 It is hardly likely that the Indians Hobbs followed into camp three days later were members of the Meeker Massacre party.

9- Rhen Cone! -- bend or corner. This is where the San Juan cuts through Comb Ridge. It is the site of the later Barton trading post where Amasa Barton was killed by an Indian a few years later.

10- San Juan Hill.

11- As far as I have been able to learn, this is the thinly account that gives William Hutchings credit for having suggested the name of Bluff City. I see no reason to doubt it. When the U.S. Post Office Department was preparing to establish an office there, the name was shortened to Bluff.

12- In his Desert News account, Hobbs states: “My father, who lived at Parowan, had promised Silas Smith, who was still at his home in Paragonah … that he would let him know when he got a letter from me saying the company got through…”

APPENDIX I

HOLE-IN-THE-ROCK PERSONNEL

B. Personnel Of The Hole-IN-The-Rock Expedition:

Gurr, William Heber (Parowan) Family Friends traveled to U.S. on Ship Lucas w/Robbs

Anna Hanson

William John

Holyoak, Henry (Paragonah) [Sarah Permelia’s Uncle]

Sarah Ann Robinson

Alice Jane

Henry John

Mary Luella

Eliza Ellen

Albert Daniel

Robb, Adam Franklin (Paragonah)

Sarah P. Holyoak

Albertus

William Heber

Robb, George (Paragonah)

Sarah Ann Edwards

Ellen Jane

Sarah Ann

Robb, William (Paragonah)

Ellen Stones

William

C. Persons Sometimes Listed As Among The Hole-In-The-Rock Company But Without Definite Proof:

Robb, Alexander

Robb, Samuel (Son of William Robb and Susannah Drummond)

Robb, Thomas